Improving Cancer Patient Care With Professor Mark Lawler

Precision medicine and immunotherapy could transform cancer treatment, yet overcoming challenges is crucial for their seamless adoption in clinical practice.

Complete the form below to unlock access to ALL audio articles.

Mark Lawler, professor of digital health, is a leader in cancer research with a focus on using the latest molecular advances and precision medicine approaches to improve patient care and address cancer inequalities on a global scale.

Lawler was invited to answer your questions about precision medicine and cancer research in Technology Networks’ Ask Me Anything session. Click below to watch the full session.

Kate Harrison (KH): What do you see as the future of tumor genomic profiling?

Mark Lawler (ML): It's a really exciting area of research. This technology allows us to do things that we wouldn't have even thought of being able to do a decade ago. Not only in terms of looking at the overall constitution of the tumor from the genomics point of view, but also being able to look at single cells.

Tumor genomic profiling has increased our understanding of different forms of cancer. But how do we practically translate this into companion diagnostic biomarker testing? One of the things we've been pushing for at a European level is to embed that genomic testing into the clinical setting. We propose that everybody is tested for their genomic profiles, so we can then decide the best treatment for each individual patient. The critical thing is knowing how to implement this precision oncology approach. We're great at doing the discovery part, but maybe not so good at the follow-through.

KH: How do you think the potential of precision oncology can be realized more fully?

ML: We've had the likes of Gleevec (imatinib mesylate) in chronic myeloid leukemia and Herceptin in HER2-positive breast cancer. They're good examples of precision oncology working, but we probably haven't seen as many successes as we would have expected. It is important that we don't base all our hopes on precision medicine and precision oncology. Surgery and radiotherapy still cure more cancer patients than precision medicine at the moment.

What we want to see is that precision medicine goes into radiotherapy and surgery, so that we have precision radiotherapy and precision surgery. I certainly don't think that precision oncology is going to replace either surgery or radiotherapy, but we need to be clever in terms of how we combine them. We've seen, for example, that immunotherapy and radiotherapy are a very good combination in certain tumor types.

I'm very optimistic about precision oncology, but I think we need to be very realistic as well – this is not going to be the panacea that will cure all ills.

It's about looking at how we use it most effectively, how we combine it with approaches that we have shown work well.

For example, advances in precision radiotherapy allow for a more precise approach that targets the tumor and doesn’t damage the surrounding tissue. We also need to use companion diagnostics in the R&D process so that we can identify the patients who will benefit from treatments.

KH: Do you think that it will be possible to design an anti-cancer drug with 100% specificity for cancer cells only?

ML: One of the challenges is moving from an approach where we understand and treat cancers individually. Immunotherapy has changed that paradigm, moving towards immunotherapy clinics, rather than colorectal cancer clinics or breast cancer clinics.

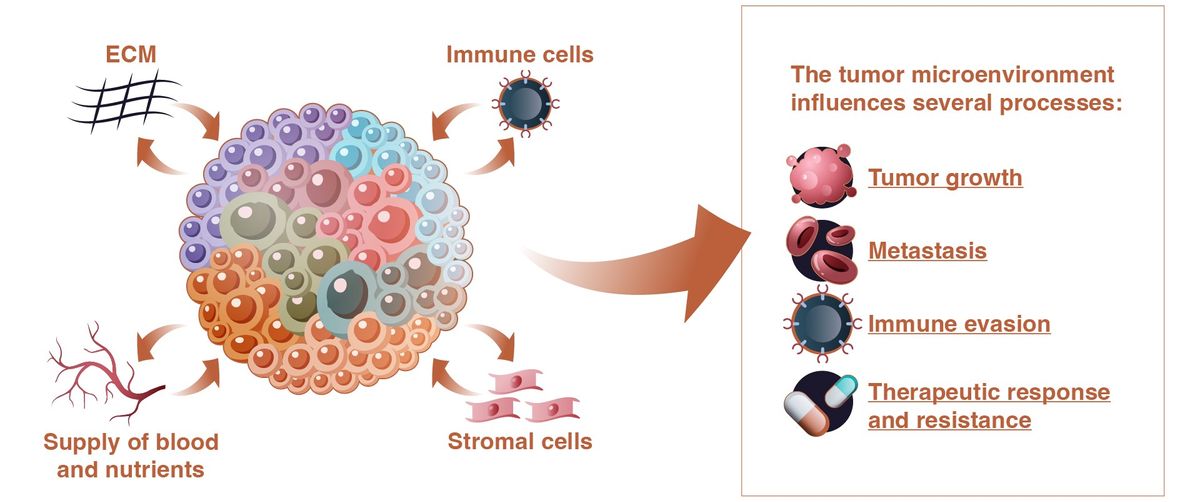

Spatial transcriptomics is going to build up an atlas of what's happening in the individual cancer cell, its interactions with other cancer cells and also with the microenvironment around it.

Figure 1: Several components interact with a tumor to form the tumor microenvironment. Credit: Technology Networks, adapted from Spatial Transcriptomics in Cancer.

Providing an approach that is off-the-shelf for everybody would be a superb vision and reality. Then, we would start to look at having cancer as a chronic disease that we can manage.

Quality of life is becoming much more important as there are more people living with and beyond cancer.

So, we need to be thinking not simply about cure or no cure, but more about how we manage cancer and reintegrate people into society.

KH: Have there been any significant insights on the relationship between COVID-19 and cancer?

ML: I’m the scientific director of DATA-CAN, which is the UK’s health data research hub for cancer. We had only just set up when the COVID-19 pandemic happened, so we rapidly repurposed our data science work to see what the impact was.

We decided to look at two things: the diagnostic pathway and the treatment pathway. For diagnostics, we looked at what's called “two-week waits” in England or “red flag referrals” in Northern Ireland. We found that 7 out of 10 people who had a suspicion of cancer were not being referred to a specialist service. Similarly, with the treatment pathway, we looked at chemotherapy appointment attendance and found that 4 in 10 cancer patients were not attending.

That data scared us so much that we immediately shared it and set up a specialist European network. We developed a 7-point plan concerning the impact of COVID-19 on cancer patients and cancer services, and we also decided to do a Pan-European study.

We found that 100 million screening tests were missed during the pandemic and 1 million cancer diagnoses may have been missed.

As a result, we've seen a tremendous impact on cancer patients presenting later with more aggressive disease because they were missed at that earlier stage during the pandemic.

In addition to the effect of services being shut down or compromised in some way, there's also the impact of having to deal with COVID-19 when you're immunocompromised. So, cancer patients and services have suffered significantly from the pandemic. In cases such as colorectal cancer, five-year survival had improved over the last 10–20 years, but now we may have set back that progress by almost a decade, unfortunately.

KH: How can diagnostic labs in low-income countries approach cancer genomics?

ML: We did a Lancet series in relation to pathology and laboratory medicine in low- and middle-income countries and how to make sure that we can deliver diagnostics that are practical, that are pragmatic, and that allow delivery at a regional or national level.

What we don't want to do is have that divide where low- to middle-income countries don't get access to these approaches. There are costs associated with it, so we can look at ways in which we do cost sharing, for example.

I think it's the responsibility of Europe and America, for example, to support cancer research and cancer care in low- and middle-income countries, so I think we should be looking at better ways to do that.

We shouldn't forget our global responsibility.

Throughout the US and Europe, we are powerhouses in cancer research and its translation to cancer care. But we shouldn't be just thinking inwardly, we should be thinking outwardly and how we can support low- and middle-income countries in diagnostic approaches, therapeutic approaches, and deliver for the patients.

If you're in Canada, and you're a kid with childhood leukemia, you have a 9 out of 10 chance of being alive in five years. If you live in Zimbabwe, that drops to a 1 in 10 chance. We are talking about treatments that are off patents, mostly chemotherapy approaches. These are curable diseases, and yet we have that disparity between the higher-income countries and low- and middle-income countries. By 2040, over 60% of deaths from cancer will happen in low- and middle-income countries, so we have a global responsibility to address that.

Professor Mark Lawler was speaking to Dr. Kate Harrison, Senior Science Writer for Technology Networks.

About the interviewee

Prof. Lawler has an international reputation in cancer research and recently received the prestigious 2018 European Health Award. His research focuses on developing a molecular understanding of cancer to improve patient care, including through precision medicine. As Associate Director of Health Data Research Wales Northern Ireland, he also has a keen interest in health data research with particular relevance to cancer.